Cyber in the Undersea

As we inch ever closer to realizing an Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT), the need for a complete understanding of the cyber threats and opportunities posed by unmanned undersea systems is urgently needed.

Two years ago I penned a FICINT vignette demonstrating the potential for microsubmarines to engage in cyber operations. The vignette focused on a two-part operation, Nøkken (named for shapeshifting creatures featured in Scandinavian folklore), and involved a Strikepod using an advanced IW payload - a Clandestine Access and Emission Module (CLAXEM) - to generate a decoy submarine signature using acoustic and magnetic emissions, and also to penetrate a Russian undersea network. Since then, there have been continued advancements in underwater communication technologies, as well as increasing deployment of underwater wireless sensor networks (UWSNs), which should cause us to seriously consider the cyber threats and opportunities that loom in the undersea.

In order to properly contextualize the cyber implications of unmanned undersea systems, I will first provide an overview of recent Blue and Red system developments, an overview of select Blue and Red concepts of operations (CONOPS), and a discussion of the technological challenges faced by actors seeking to operate in the undersea.

BLUE DEVELOPMENT CONTINUES APACE

The United States and its allies continue on course to fielding a range of advanced undersea systems (vehicles, sensors, and related communication, energy, processing devices and infrastructure) intended to increase undersea situational awareness, counter undersea threats, and enable freedom of maritime maneuver in all theaters of operations.

-

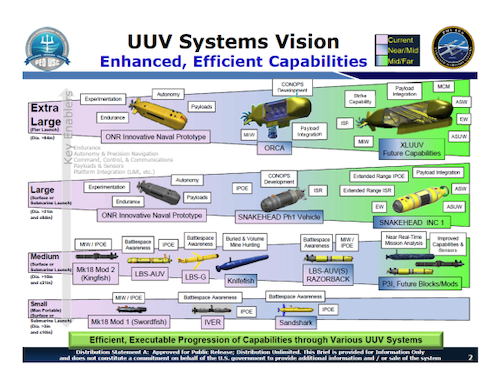

The United States Navy continues to focus on developing a family of UUVs of varying sizes and capabilities. Boeing is currently under contract to build four Orca XLUUVs (while the Pentagon's Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) recommends augmenting the fleet by operating as many as 50), which are scheduled to join the fleet as early as 2022. Work on the large UUV Snakehead continues, and a consolidated medium UUV (Razorback/Kingfish) program will produce a surface-launched expeditionary mine countermeasure variant, and a submarine launch/recovery variant to be deployed via torpedo tubes or payload modules.

-

The Royal Navy is pursuing an unmanned undersea capability, and is seeking its own XLUUV. The initial prototype/test vehicle will be based on the MSubs S201, with a plan to eventually procure a 30-meter vehicle based on the Manta or Moray that will be optimized for ISR, payload delivery, and undersea combat. It's unclear what CONOPS the Royal Navy may have in mind at this time, but a fleet of XLUUVs would affordably augment the Royal Navy's current fleet of seven attack submarines, enabling increased monitoring of Russian undersea operations in the North Atlantic.

Manta concept by Msubs. | Source: Msubs.com

- At MADEX 2019, the ROK navy unveiled a large displacement UUV designed specifically for anti-submarine warfare (ASW). The ROK ASWUUV is approximately 30 feet long, can operate to 300 meters, and will utilize an innovative fuel cell power system providing an endurance of approximately 30 days. The ROK is said to be developing a wide range of UUVs that will leverage AI and big data, with a particular emphasis on ASW and augmenting KSS-class submarines in countering North Korean undersea threats.

Source: NavalNews.com

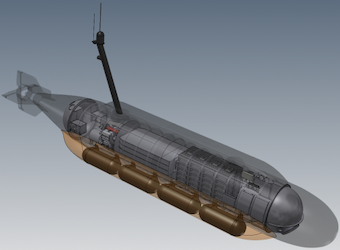

- This month, thyssenkrupp finalized its research for the Modifiable Underwater Mothership (MUM), a highly modular XLUUV system which can be configured for various missions, including ISR, minelaying, or ASW. The vehicle is 25 meters in length, can carry 4 heavyweight torpedoes or 9 mines, and is powered by state-0f-the-art fuel cell technology providing in excess of 400 hours.

Source: thyssenkrupp

RED DEVELOPMENT IS ACCELERATING

Adversaries are expanding their footprint in the undersea, fielding new systems and capabilities at an accelerating rate.

- In early May, a Russian UUV, Vityaz-D, conducted the first autonomous, unmanned voyage to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. The vehicle interacted with a seabed "bottom grab" station, which then communicated with the host vessel on the surface via a "hydroacoustic channel." The Advanced Research Foundation (the Russian equivalent of DARPA) recently stated that the vehicle would be transferred to the Ministry of Defense.

Vityaz-D seabed station (L) and UUV (R).

- Development of Poseidon, Russia's nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed intercontinental "doomsday" torpedo/UUV, appears to be on track. The lead boat of a new class of submarine, Khabarovsk, based on the Borei SSBN and purpose-built to host six Poseidons, is scheduled to be floated out this month. Belgorod, a modified Oscar II "undersea mothership" which, in addition to gathering intelligence and hosting special operations submersibles, will also carry up to eight Poseidons, is currently undergoing sea trials and is expected to join the Northern Fleet sometime this year. A scheduled test firing of Poseidon in the White Sea is scheduled for this fall.

Poseidon with host platform Belgorod.

- In March, China deployed a dozen Haiyi gliders from the oceanographic research ship Xiangyanghong 06 to the Indian ocean on a scentific research expedition. The gliders purportedly travelled 12,000 km and collected some 3400 environmental observations over a period of approximately two months. The Chinese appear to have a great affinity for gliders, notching several high-profile depth and distance records, and claim to have achieved real-time undersea communication. While there are operational limitations to gliders, it is possible that they could be configured as an ASW picket, providing early warning and cueing for surface and/or air assets.

- In October, 2019, during the nation's 70th anniversary celebration parade, China unveiled, among other pieces of military hardware, a large UUV marked "HSU-001." (My analysis of HSU-001 can be found here.) Though there have been no official statements regarding its capabilities, CONOPS, or operational status, China has alluded to such missions as seabed warfare, special operations, and ISR.

- Late last month, the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGCN) took delivery of over 100 new vessels, including what appeared to be an extra-large UUV. While unlikely to have advanced beyond the prototype stage, it underscores the IRGCN's ambition to build or acquire an unmanned undersea capability. Iran has leveraged unmanned aerial systems to great asymmetric effect, and so it should come as no surprise that the IRGCN would seek to bolster its undersea warfare capability through the deployment of unmanned systems.

- Iranian proxies stand to benefit from Iranian R&D efforts in this space, including indigenously developed or illicitly acquired systems. But Iran could also benefit from the ambition and engineering know-how of its proxies. In 2016, the workshop of Hamas drone engineer Mohammad al-Zawahri was found to contain a UUV prototype.

Source: Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs

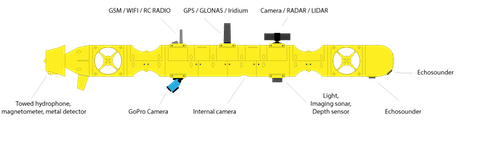

- As with unmanned aerial systems, it is entirely possible that undersea systems could be weaponized by nonstate actors. To be sure, the barriers to entry are greater in the undersea than in the air, and this will narrow the field. But the undersea is becoming more accessible all the time. Consider the Amethyst AUV Platform, a 3D printable UUV framework that provides hobbyists, educators, researchers, and enthusiasts with an inexpensive, user-friendly platform for crafting their own autonomous undersea vehicle. Though there are still obstacles to fielding an effective weapon using this kind of platform (and I am in no way suggesting that it poses any unique risk), it is indicative of how easy it could be to fashion an "undersea IED" or malicious undersea network node using commercially available hardware and software.

Source: Beobachtung

OPERATIONAL CHALLENGES PERSIST (FOR NOW)

Unmanned undersea operations continue to be limited by the complex, dynamic conditions of the ocean environment and the unique operational constraints they engender. Three critical capabilities - communication, energy, and autonomy - will drive future developments in this domain.

Communication

Without access to the RF spectrum, undersea systems rely principally upon acoustic or optical (laser) technologies for submerged communication, both of which come with significant tradeoffs in terms of range, bandwidth, and clandestinity.

- COTS acoustic modems convert digital data into sound waves, and are currently the cost-effective technology of choice for underwater communication, providing anywhere from hundreds of meters to thousands (km), depending on environmental conditions and the sophistication of the technology. Premium products offer maximum baud rates of around 15,000 bps - less than early Internet dial-up modems which, while adequate for most scientific or industrial purposes, would likely prove inadequate for most undersea warfare missions. Acoustic communication is also detectable, making it unsuited to covert operations.

Teledyne Benthos Compact Modem

- Optical communication systems utilize blue or blue-green lasers and light emitting diodes to transmit data. Optical communications are capable of much higher baud rates - Mbps versus Kbps for acoustic - but are generally limited to tens of meters. Australia’s Defence Science and Technology Group (DST) recently invested in Sonadrdyne's BlueComm optical communications system, currently the only COTS technology available.

Sonardyne BlueComm 200

- TARF (Translational Acoustic-RF Communication) is an experimental, hybrid acoustic/electromagnetic form of communication. When a submerged vehicle broadcasts an acoustic message toward the ocean surface, sound waves produce tiny ripples on the surface of the water. These disturbances form the ones and zeros of binary communication, which can then be detected by the surface search radar of orbiting aircraft.

Until recently, there was no common standard to facilitate undersea communications, with each modem manufacturer utilizing their own proprietary system. Over a period of several years, NATO's Center for Maritime Research and Experimentation (CMRE) developed JANUS, a communications protocol for undersea vehicles, which became a NATO standard in 2017. Like Bluetooth or Wi-Fi for the undersea, JANUS enables interoperability between military, scientific and industry systems.

Energy

In order to provide persistent coverage, particularly in contested or denied areas, unmanned undersea systems require access to a high-density power source, either onboard or via recharging stations deployed in situ. Gliders are the most energy efficient UUVs by far, able to operate for weeks or months at a time on a single charge, but are limited in terms of payload and operational capabilities. Small or medium UUVs utilize standard lithium-ion batteries which provide anywhere from 24 to 72 hours of charge, depending on mission, and require several hours to recharge. Large and extra large UUVs will house more robust power systems, enabling longer range and endurance, and may incorporate fuel cells, or AIP - Air-Independent Power (also called Air Independent Propulsion). The Boeing Orca is powered by a conventional diesel-electric system, similar to conventionally powered manned submarines, and will provide an operating range of 6500 miles. While progress continues to be made in this space, unless the demand for power is adequately met, energy density will be a limiting factor in unmanned undersea operations.

Autonomy

Without reliable, high-bandwidth communication enabling ongoing, real-time communication with operators, unmanned undersea systems will rely heavily on autonomy and artificial intelligence, and as operations increase in sophistication, intensity and complexity, the greater will be the need for trustworthy systems that can "OODA" in a dynamic and challenging environment. The U.S. Navy is developing the Unmanned Maritime Autonomy Architecture, a set of common interface controls and core software technologies for autonomous maritime systems, while CMRE is developing an open architecture for the development of task algorithms in networked UUVs. Many questions and uncertainties surround the deployment of artificial intelligence, particularly in the service of military operations. Even the very definition of autonomy/AI is the subject of some debate.

BLUE CONOPS ARE MANIFOLD

The range of Blue concepts and ideas is quite extensive, and will continue to evolve. What follows are the best representations of what the future holds.

Submarine Launch and Recovery

UUVs are launched and recovered via torpedo tube, the Virginia Payload Module or an SSGN missile tube using the Universal Launch and Recovery Module (ULRM). The current RFP for a consolidated (Kingfish and Razorback) MUUV calls for two variants, an expeditionary MCM variant, and one for submarine launch and recovery, ostensibly for ISR or ASW (or, eventually, CUUV and Strike) and deployed in a manner envisioned by DARPA's Mobile Offboard Clandestine Communications & Approach. The ULRM may also be used to deploy XLUUVs in accordance with the Advanced Undersea Warfare System (see below).

“Moor-Pedos”

In the December, 2019 issue of USNI Proceedings, retired USN Commander Brian Dulla outlined the concept of a "Moor-Pedo," essentially a dormant autonomous mine that is moored to the seabed in international waters and activated upon receiving a signal via surface buoy. The U.S. Navy is currently developing a moored torpedo system called Hammerhead, which borrows heavily from the Mark 60 CAPTOR mine, utilizing an encapsulated Mk 54 torpedo integrated with advanced sensors and signal processing. The line between torpedo, mine, and unmanned vehicle will continue to blur until the three converge into a single platform.

Undersea Swarms

Aerial drone swarms are widely expected to transform warfare, and will soon be fully operationalized. Undersea swarms, while possible, will be limited by environmental conditions and technological capability, as swarming requires ongoing, real-time communication. SwarmDiver is a collaborative USV/UUV platform developed by Australian company Aquabotix, which demonstrates the viability swarming in a maritime environment.

Strikepods

Envisioned by Strikepod Systems, a Strikepod is a distributed network of UUVs (Atom-class microsubmarines) programmed to execute missions of varying scale and complexity, and can be comprised of any number of vehicles depending on the nature of the mission at hand. A Strikepod is similar to a swarm in that the vehicles are working together to accomplish a common mission, but different in that there is a hierarchical relationship between the component vehicles. There are three variants or "modes" of the Atom-class:

- Rogue - Command & Control

- Remora - Target Prosecution & Strike

- Relay - Communications

Each vessel is mode-configured prior to deployment, but is capable of dynamically reconfiguring on the fly, providing adaptability, redundancy, and expendability. Working within a broader grid of ships, manned/unmanned submersibles, seabed sensors, Strikepods would provide near-complete undersea situational awareness, persistent access to denied areas, and wide operating coverage. A Strikepod represents the convergence of several missions under one platform - ISR, ASW, MCM, offensive mining, and undersea strike.

Hydra

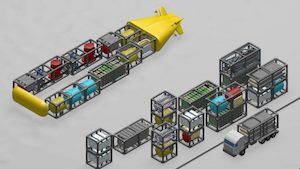

DARPA's Hydra is an umbrella "concept of concepts" that envisions using large or extra-large vehicles to transport and deploy a range of undersea payloads such as small UUVs, seabed sensors, mines, Forward Deployed Energy and Communications Outposts (FDECOs), or Upward Falling Payloads (UFPs).

Transformational Reliable Acoustic Path System (TRAPS)

Developed under DARPA's Distributed Agile Submarine Hunting (DASH) initiative, TRAPS is a network of fixed, deep ocean sensor nodes, acting as "subullites" (ocean satellites) providing large fields of view to detect and localize submarines operating overhead. To complement this effort, DARPA has also developed a mobile platform, the Submarine Hold-at-Risk (SHARK) UUV. TRAPS would complement the numerous seabed sensor systems already in place through the IUSS, including the Fixed Distributed System (FDS) and SURTASS.

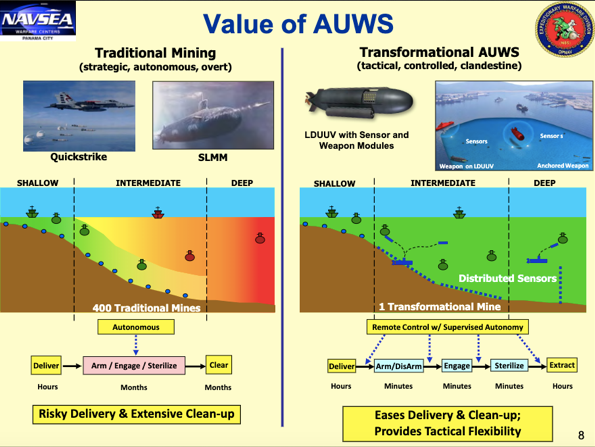

Advanced Undersea Weapons System (AUWS)

At least ten years in the making, AUWS is a unified vision of the U.S. Navy's thinking with regard to unmanned undersea systems, and is indicative of the renaissance happening in mine warfare. The concept envisions a flexible, scalable, integrated network of sensors, communications, vehicles, and effectors that can be deployed anywhere, anytime, via an XLUUV "truck" deployed from an SSGN Universal Launch and Recovery Module, or a Virginia Payload Module. An NPS report can be found here.

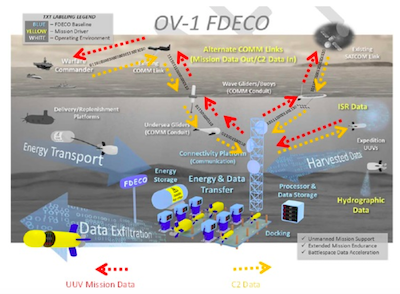

Forward Deployed Energy and Communications Outpost (FDECO)

A FDECO is a network of undersea communications, recharging, and data transfer infrastructure enabling persistent coverage in a forward area where the deployment and recovery of UUVs could be hazardous to manned platforms.

Mine Countermeasures/Disposal

A mission rather than a concept of operation, MCM has received perhaps the most attention over the past five years, as this is an area where unmanned systems could provide the most immediate and tangible payoff by removing sailors from the minefield, greatly reducing the risk to both man and machine. CONOPS involve the standoff launch and recovery of UUVs or ROVs via manned surface platforms, or completely unmanned USV/UUV integrations that provide mine detection, localization, and neutralization.

The Raytheon Barracuda mine neutralization system.

RED CONOPS ARE ELUSIVE

While little has been expressly written regarding concepts for deployment and operation of unmanned undersea systems, a review of open source materials reveals that our adversaries are considering similar designs for the undersea domain.

China: "The Underwater Great Wall"

The "Underwater Great Wall" was proposed by China State Shipbuilding Corporation as an effective means to realize China's A2AD aspirations for the South China Sea - essentially an integrated barrier of UUVs, seabed sensor arrays, energy stations, and data processing nodes, networked together to provide real-time data and intelligence to surface and land-based commanders. Not surprisingly, the Underwater Great Wall borrows heavily from U.S. CONOPS, specifically FDECO, but it is reasonable to assume that the network will incorporate gliders and HSU-001 as well. It is also reasonable to assume that the PLAN will continue to borrow heavily from USN concepts, and thus we may look to our own technologies and concepts as a way to forecast what the PLAN may roll out in the future.

The Underwater Great Wall.

China: The Blue Ocean Information Network

China has established a network of fixed and floating outposts in the region between Hainan Island and the Paracels. While the stated purpose is environmental monitoring, the military implications are clear. Only surface structures are visible (referred to as "Ocean E-Stations," "integrated information platforms," and "island reef-based integrated information systems"), but a paper published in the Chinese Academy of Science's Journal of Automation suggests that the Network will eventually be comprised of sensory arrays, UUVs, USV, and associated energy/data/communications systems and infrastructure. See the CSIS/AMTI full report here.

Russia: Multipurpose Oceanic System

Much attention has been given to Poseidon, variously described as an autonomous, intercontinental, nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed UUV/torpedo. Poseidon is part of Russia's somewhat (perhaps deliberately) ambiguous "Multipurpose Oceanic System," which appears to refer primarily to the Poseidon-Khabarovsk and Skif (a seabed variant of Poseidon) platforms. Russia is also aggressively developing a range of small and medium UUVs intended for ISR, ASW, MCM, and even attack/strike, as well as a SOSUS-like Arctic sensor array codenamed Harmony. It would seem that Russia's vision for the undersea is, like the United States and China, an integrated network of manned submarines/submersibles, UUVs, and seabed infrastructure.

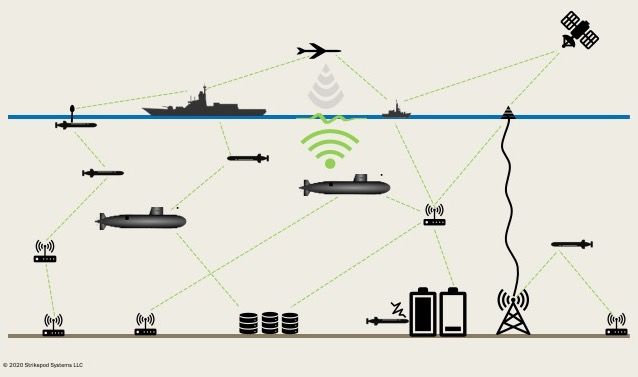

VARIATIONS ON A THEME: A UWSN

Whether of Blue or Red origin, each undersea CONOPS is a form of underwater wireless sensor network, or UWSN, the framework for a broader Internet of Underwater Things (IoUT). Much as the Internet of Things (IoT) will connect objects of everyday living, and the Internet of Battlefield Things (IoBT) will improve Army situational awareness by connecting an array of sensors and analytic devices, the IoUT will connect a network of vehicles, sensors, energy depots, data processing centers, communications nodes, and related infrastructure in order to gather and transmit information through the water column.

An Underwater Wireless Sensor Network

Much as RF wireless sensor networks have enlarged the attack surface for malicious actors, the deployment of UWSNs and their integration into the broader undersea warfare framework will significantly expand the maritime attack surface for Blue and Red alike. This has particular implications for the U.S. Navy as it moves toward operationalizing Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO).

NETWORK THREATS WILL ABOUND

Like any wireless network, a UWSN presents numerous points of entry for malicious actors to exploit. Given increasing communications and data transmissions, shared protocols, open network architectures, and an opaque operating environment, there will be numerous attack vectors available to both Blue and Red in the undersea domain. While there is some overlap, these operations break down roughly into three categories: physical/kinetic, intrusion, and deception.

Physical/Kinetic

While not expressly a cyber operation, a kinetic attack on cyber infrastructure could be just as damaging if not more so, as the physical destruction could greatly prolong the recovery process.

-

Undersea Cables - Transoceanic cables carry the majority of Internet traffic, including trillions of dollars in financial transactions each day. The threat to these cables is well documented, as is the potential disruption to the global economy due to damage or severing. Russia is assumed to have a sophisticated cable cutting/tapping capability, and its submarines have been rumored to be operating near undersea cables in the North Atlantic. China has been laying cables in the South China Sea, connecting various island outposts, and likely powering a wider undersea surveillance system which could be targeted during open hostilities or during below threshold, gray zone operations. Israel is currently linked to the Internet via three undersea cables, and will also be a conduit for Google's multi-national Blue-Ramen undersea/overland fiber optic cable. These could be attractive targets for nonstate actors with an unmanned undersea capability.

-

Seabed Server Farms - In 2018, Microsoft pioneered the idea of placing server farms on the ocean floor as both an environmentally friendly and economic solution to data center cooling. Because these structure are located on the seabed, there may be a sense that they are immune from any physical attacks. However, given trends COTS technologies, and the willingness of nonstate and rogue actors to fashion explosive devices using, these facilities would be vulnerable to attacks using homebrewed "undersea IED"-style UUVs or, more likely, ROVs. These farms will be located in relatively shallow, coastal waters, and could be easily located using a combination of OSINT and onboard COTS sensors. A shaped charge would breach the pressure vessel, flooding it with seawater and causing irreparable damage to the infrastructure and data housed within.

-

Surface Gateway Nodes - Air, land, surface, and space assets will utilize buoys, surfaced UUVs, or small USVs to access undersea networks, any of which will be vulnerable to kinetic attacks. Surface gateways may be somewhat protected due to their size, but could be detected and localized by surface search radar or ESM collection platforms.

-

"Catch and Release" - UUVs, floating sensors, and even fixed seabed infrastructure will be vulnerable to capture, potentially providing adversaries with a wealth of S&T intelligence, including access to critical information systems. Unlike China's high profile seizure of a U.S. LBS glider in 2016, future seizures will likely be covert, and may occur without knowledge. With the advent of edge computing, this will become even more of a concern, as vehicles and infrastructure will contain sensitive data processing algorithms and AI models.

-

"Honey Pot" - An adversary could insert a dummy data processing node into the network, deceiving UUVs into utilizing the interface for communication or data exfiltration.

Intrusion

An intrusion attacker seeks access to a network with the intent to eavesdrop, access data, or otherwise destabilize the network through the introduction of worms, trojans, spyware, or a flood of traffic. Some ways a UWSN could be compromised by intrusion include:

-

Uninvited Guests - Adversary submarines make regular appearances during maritime exercises to gain valuable acoustic and signals intelligence, but the risk of detection is high. A UUV, or several UUVs dispersed throughout an exercise area would be significantly harder to detect, and could be charged specifically with intercepting acoustic communications. This could be particularly effective during exercises such as Dynamic Mongoose, REP(MUS), Unmanned Warrior, or ANTX, where UUVs are increasingly integrated into operations and put through their paces.

-

Stowaways - Using a compromised Wi-Fi network during manufacturing, testing, or maintenance, an adversary could install malware designed to transform a UUV or sensor into a malicious node. Once deployed, the node could gather data and intercept communications, making periodic covert transmissions to a nearby adversary vehicle. Malware could also make its way from the infected system onto the submarine during integration with shipboard systems. In 2014, Naval Sea Systems commander, Vice Adm. William Hilarides alluded to the cyber risk posed by offboard networks to submarines.

-

Vehicle/System Hijacking - A malicious actor could gain control of entire vehicles or systems using either stowaway methods, or spoofing (see below). There is precedent for such an act. In 2011, an Iranian cyber warfare unit allegedly took control of a CIA RQ-170 Sentinel and directed it to land on an Iranian airstrip in Kashmar. There are questions as to what method of attack may have been used (or whether it was in fact a cyber attack that brought it down). Iran claims to have jammed the drone's communication, forcing it into autopilot, and then, in a deception-style attack, spoofed the drone's GPS. Since undersea vehicles will, more than surface and air, be relying more on autonomy and artificial intelligence, a hijacker would require access to the underlying control algorithms underpinning the AI.

-

AI Hijacking - Unlike AI manipulation (see below), hijacking an AI would entail replacing the entire Blue model with a Red one, effectively gaining complete control of system operations. While perhaps more ambitious and requiring a higher level of operational sophistication, the advent of edge computing, with end nodes and devices hosting data processing algorithms as well as the AI model itself, may place this kind of attack within range of low-end actors.

Deception

"All warfare is based on deception." In the coming era of information dominance, autonomous systems, and artificial intelligence, Sun Tzu's words will perhaps come to resonate more than ever. In the challenging undersea domain, the need to leverage, and counter, deception and manipulation will be enhanced by the tools and techniques of cyber warfare, including:

-

Spoofing - Whenever possible, UUVs rely upon GPS fixes for navigation, using inertial navigation as a fall back. This impacts mission timing, energy consumption, and clandestinity as it requires the vehicle to surface periodically, exposing itself to detection by surface or air surveillance. DARPA is working to bring GPS to the undersea via POSYDON - Positioning System for Deep Ocean Navigation, a network of seabed transmitters. By computing the absolute range to multiple signals, a UUV can obtain continuous, accurate positioning without surfacing for a GPS fix. The vulnerability here lies in the acoustic beaconing. A malicious actor could turn off existing POSYDON beacons, or, using a malicious node attack, masquerade as a beacon, resulting in false location readings for undersea vehicles. (Depending on the size of the node and related infrastructure, the physical unit could be vulnerable to covert kinetic attack as well.)

-

Decoy - Similar to spoofing, an adversary vehicle could insert malicious code that produces false targets on host sensor systems. Likewise, in an hybrid EW-cyber attack, an adversary vehicle could force false sensor inputs by accessing an onboard digital library to broadcast acoustic (or magnetic) signatures using an onboard emulator. (Similar to modern torpedo countermeasures.)

-

Man-in-the-Middle - In a man-in-the-middle attack, a Red network node impersonates a Blue node, and deceives other Blue nodes into believing they are communicating with each other when in fact they are communicating with Red. Red can then intercept or disrupt network communications, or poison the data stream. Red could theoretically join a scientific or industry UWSN operating in Red-denied waters, exploiting the interoperability provided by JANUS to access host sensors and conduct a covert IPOE operation.

-

AI Manipulation - While the nature and extent of AI control of undersea operations is still up for debate, it is possible to imagine how attacks on a maritime AI might unfold. One way to fool an AI would be to poison the dataset on which it bases its decision making. For example, a malicious actor could poison a MCM AI's dataset of seabed mines, causing it to identify ordinary organic objects as targets to be neutralized, or, conversely, identify actual mines as benign. The damage would be compounded to the extent there are shared datasets involved - for example, if an attacker poisoned a dataset of acoustic signatures used by both unmanned undersea and unmanned surface systems. A more low-tech approach would be to lay a dummy minefield with objects that manipulate the AI's algorithms, causing it to expend time and resources interrogating false targets, or ignore live ordnance. AI manipulation attacks would be particularly debilitating in that they may be extremely hard to detect, or even undetectable. If detected, the model would effectively have to be retrained with a sanitized data set, and command trust would be severely, if not irrevocably, damaged.

STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS

Manned submarines will be increasingly vulnerable to cyber operations as unmanned vehicles and seabed infrastructure become fully integrated into undersea warfare operations via UWSNs.

Due to infrequent and short-burst communications, submarines have historically been less vulnerable to cyber threats, with their main risk exposure coming from manufacturers and contractors. (But they are sometimes mistakenly believed to be air gapped, and therefore largely immune.) As submarines increasingly deploy and recover UUVs and seabed infrastructure via torpedo tube, DDS, or the Virginia Payload Module (VPM), and communicate and share data via acoustic transmissions, the cyber vulnerability of manned platforms will increase dramatically.

Through targeted cyber operations, an adversary could employ UUVs to deceive a host UWSN into falsely sensing the presence of an SSN or SSBN, thereby eliciting a strategic reaction on the part of the host.

Submarine intrusions have historically been used for strategic signaling or to influence national political opinion. The Soviets (in the 1980s) and Russia (in 2014) invaded Swedish waters. Periscopes (presumably Russian) have been sighted by fisherman off the coast of Scotland, not far from Faslane. In 2006, and during a visit to China by then-Pacific Fleet Commander and future CNO Gary Roughead, a Chinese Song-class submarine surfaced just five miles from the USS Kitty Hawk. While these intrusions have (mostly) been observable, it could be possible to use unmanned systems acting covertly to emulate the presence of manned submarines either through intrusion (malware) attacks, or through a hybrid EW-cyber decoy operation. Thus, it could be possible, for example, for a Russian UUV to deploy in Chinese territorial waters to emulate the signature of a Virginia-class submarine to foment a crisis. Or for a U.S. UUV to deploy in Russian territorial waters to emulate the signature of a Chinese Yuan-class submarine to drive a wedge between Russia and China.

Red's expanding undersea presence combined with the development and proliferation of increasingly sophisticated underwater technologies will foster gray zone operations in the undersea domain.

With its trademark deniability and non-attribution, the gray zone utility of cyber operations is well known, and it will continue into the undersea domain. But given the vast, opaque, and largely unmonitored nature of the undersea, cyber operations conducted there may enjoy a kind of "double cover" in that the adversary will enjoy a freedom to exploit both virtual and physical attack vectors while benefiting from anonymity. For example, a state-sponsored actor could use a COTS ROV to attack a seabed server container, resulting in data and equipment destruction, market turmoil, and political-economic uncertainty. Russia could insert a malicious node (UUV) into a Dynamic Mongoose exercise and execute a Man-in-the-Middle attack to gather SIGINT related to NATO undersea communications. The undersea environment would render these attacks, and their resulting cyber effects, largely untraceable.

UWSNs will give rise to a host of new vulnerabilities and threats, greatly expanding the U.S. Navy's attack surface, and introducing an array of new attack vectors.

Unmanned undersea operations will effectively open a new front in cyber operations. This has particular implications for DMO - a system of systems / network of networks, with a high degree of integration between systems, forces, domains. Moreover, while perhaps the stuff of science fiction, it is not beyond the realm of reality to envision a single artificial intelligence that is distributed across platforms and domains to integrate operations within a single command and control entity. In my Admiral Lacy oral history series, there is an AI, "Falken," that oversees the integrated autonomous operations of unmanned surface and unmanned undersea vehicles (Part II, Part III). An overarching Chinese AI, dubbed "Laoshi," was featured in a recent RAND wargame to test assumptions regarding the use of artificial intelligence in conflict. Thus, while the "mainstream" cyber implications of DMO generally may be quite evident, the enlarged attack surface engendered by unmanned undersea operations, as well as the integrated AI that they could inspire, may not.

CONCLUSION

The proliferation of underwater wireless sensor networks and the coming Internet of Underwater Things will give rise to new cyber threats, vulnerabilities, and opportunities, exposing new virtual and physical attack vectors in an environment that offers both anonymity and deniability. Although significant technological barriers to entry will persist in the short term, they will continue to erode as market forces and security considerations drive innovation forward. It is critical to anticipate and understand how cyber operations will unfold in this unique and challenging environment, as well as the broader strategic challenges they will present.